Jonny

—

October 13, 2023

—

ANTI-

Somewhere inside of all of us, there’s a place where our deepest hurts forever cry out to be soothed. The way people failed us as children, the jagged cliffs we stumbled down when we went looking for fertile fields — they stay with us, singing through the body long after the initial shock. It can feel easier to sideline that hurt, to wrap it up and set it aside and try to get on with life. But life only reveals itself through healing, and healing only comes when we pore over the heaviest loads we carry. It takes courage to dive in, and patience and gentleness and tenderness, but it’s lifesaving. It opens the world. On his latest album as The Drums, New York-based indie pop artist Jonny Pierce plunges into the work of healing from childhood trauma and the long shadow it casts over adulthood. The sparkling, eponymous Jonny unfurls a love letter to a galaxy of younger selves, all hungry to be nourished, all rejoicing now that they finally get to belong.

The songs on Jonny emerged out of a radically new way of writing for Pierce. On past Drums albums, he’d prided himself on his stark efficiency. “I could just get in front of my computer for two minutes with a guitar and bang out a track,” he says. “A lot of my self-worth was built into that.” But as he began exploring a different way of relating to himself in therapy, his relationship to his art shifted, too. Everything slowed, letting new and delicate shapes come to light.

“I began the work of being gentle with myself. Things overall started getting softer. There was a sweetness around me,” Pierce says. “When I went to create this new album, I brought that tenderness with me. I let the process be really slow when it wanted to be slow. I would go in every day or once a week or once every two months and chisel a little bit. And I would listen to my body. And when I was done, I was done. My body would tell me, ‘Maybe today it’s just writing a bass line for a verse. And that’s okay, that’s enough. Your worth doesn’t change based on how prolific you are.’ There was so much love in those thoughts, in that space, in the creation.”

That newly expansive space allowed Pierce to write towards parts of himself that he’d previously blanched away from: the scared, hurt kid who worked hard to survive an abusive home, the young adult who peered out at the world through a hardened shell. Facing parental rejection in his most formative years, Pierce learned loneliness as a survival strategy. On the springy, guitar gilded “Isolette,” he delves into how that seal between himself and the world both offered a kind of safety and led him into emotional starvation.

“The French word for ‘incubator’ is ‘isolette,'” Pierce notes. “My mother experienced what is referred to as a birth trauma when she was pregnant with me. A doctor broke her water without her consent, and she immediately went into painful, traumatic labor. I was born prematurely. They rushed me into an incubator where no one was able to touch me. Over the course of the pandemic, I took a lot of psych courses. In child psych, I learned that it is of utmost importance for a mother to have skin contact with her baby. It’s fundamental for bonding. We didn’t have that. The love and trust you get from that initial bonding influences how you feel love and trust in future relationships. My mother had been violated at the time of my birth and I believe I became a symbol of that trauma. She detached from me emotionally, so on many levels I often feel like I never really left the isolette.”

Throughout his adult life, Pierce found himself either detaching completely from others or melting into them to the point of losing himself. “Better” drapes a glimmering hook over lyrics about lurching out of an ultimately codependent relationship and retreating into that old reliable loneliness: “My solitude loves me better than you do,” he sings. Conversely, on the blissful, celebratory “Obvious,” Pierce steers himself into the beautiful interdependence that can flower when you neither lose yourself nor fortify yourself against another person. Love blooms in openness without obliteration, a truth that “Obvious” sings from the rafters.

A series of minute-long vignettes ground the album in gentle introspection as Pierce sings directly to his younger selves. “There’s a little child that lives in me / I just wanna protect him always / So sweet, so tender, still looking for his mother / He deserves only flowers,” Pierce sings on “Protect Him Always” against strums of acoustic guitar and string flourishes. On the twinkling, electronic “Little Jonny,” he promises his child self, “I’m never leaving your side.” These moments flow into the larger, more structured pop songs throughout the album, tethering them to a wellspring of sweetness. The relationship we have with ourselves forms the foundation of the relationship we have with others; with these self-addressed interludes, Pierce offers a window into how the inner world feeds the outside in turn.

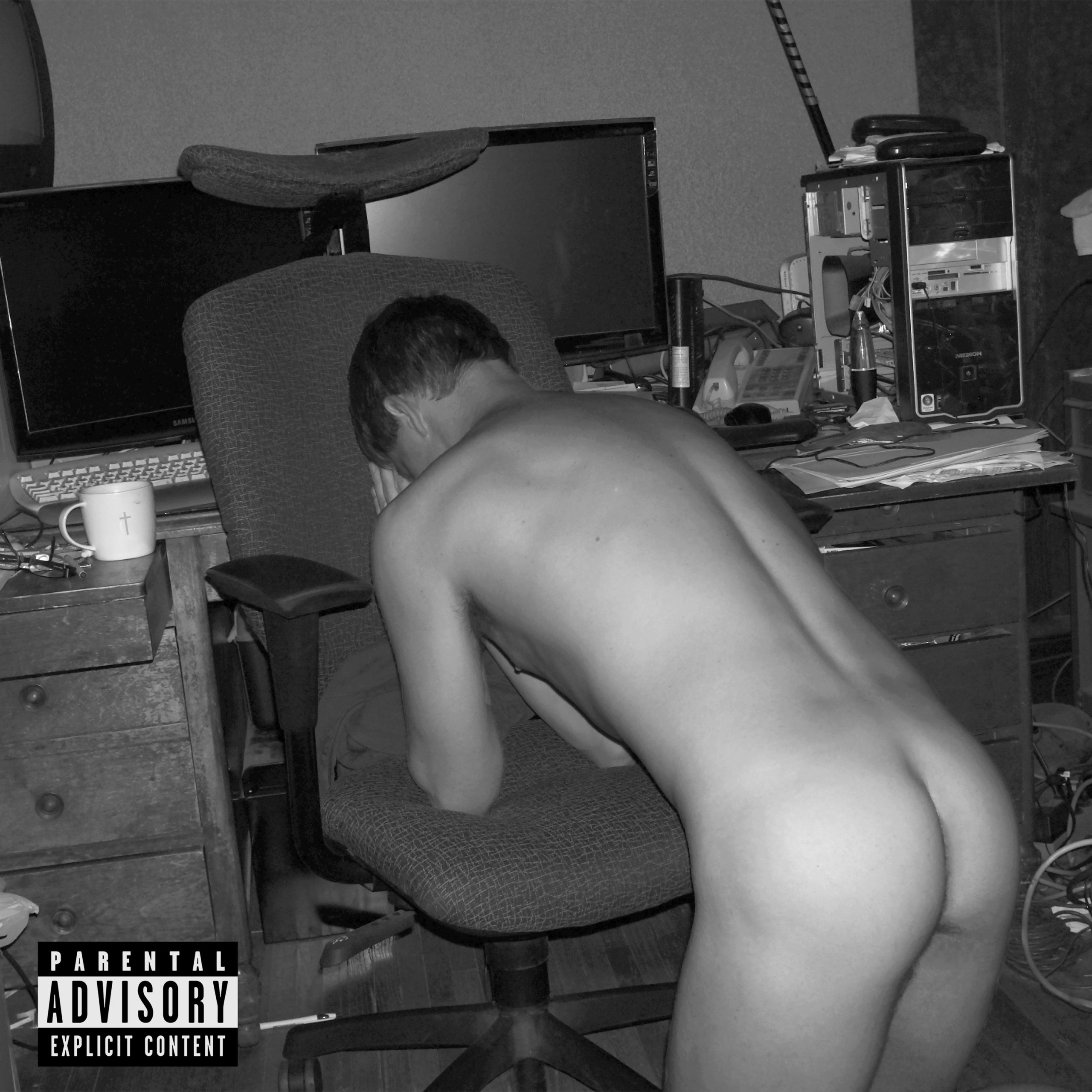

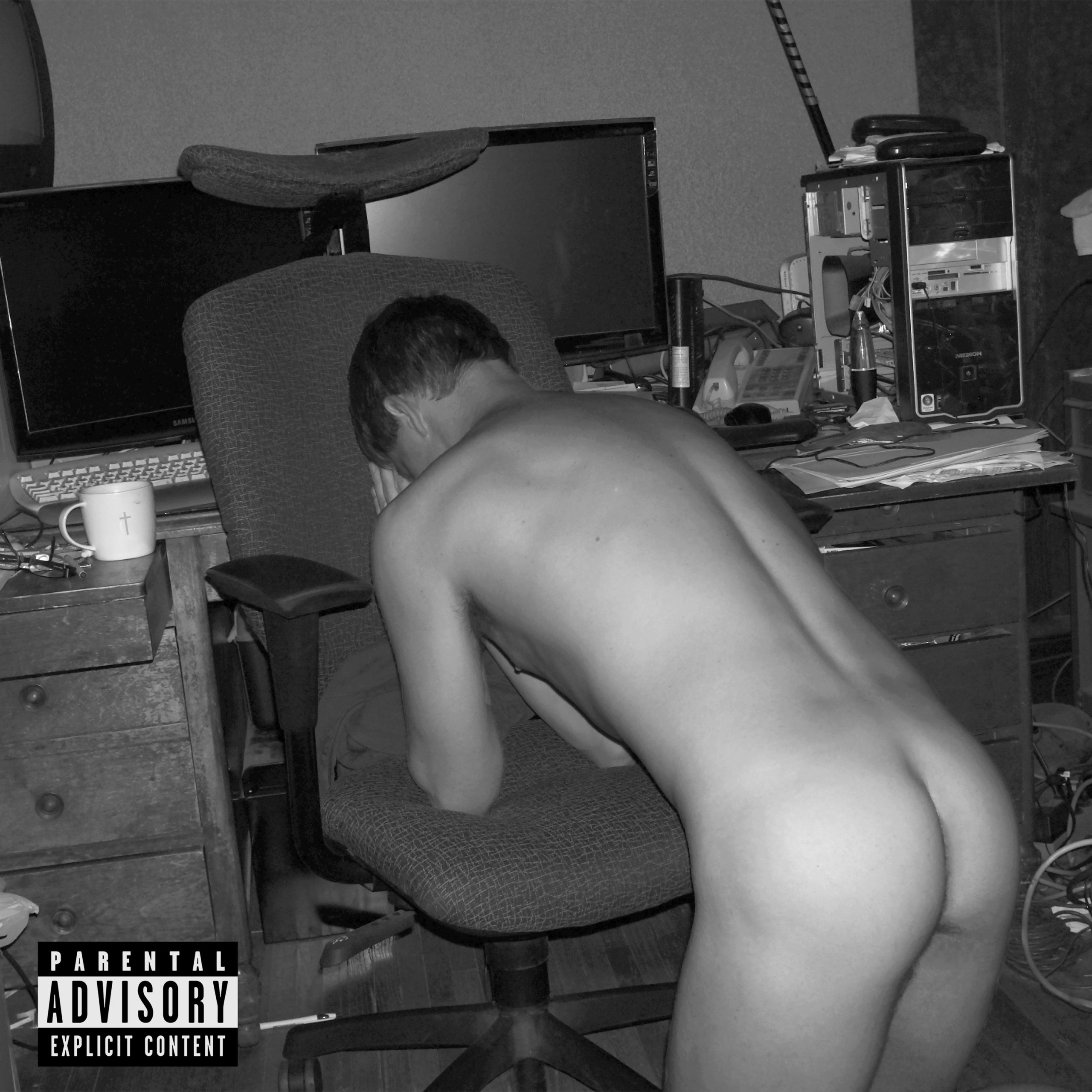

The cover of Jonny is a naked self-portrait, taken in his father’s office in Pierce’s childhood home a decade ago. “I kept feeling this need to drive upstate. I had a camera with me and a tripod. I wasn’t sure what I was going to do, but I felt a hand guiding me, or pushing me. I needed to do this,” Pierce says. “I timed it when I knew my parents would be away at service. My birth father is the head of what I call a cult — he calls it a church. I entered my childhood home and I began to undress. I didn’t know why. I began to photograph myself with a self-timer, naked in all the places in that house where something significant and usually traumatic happened to me as a young boy. I’d done a lot of thinking about this, and I still have questions, but I think I have some answers, too. For instance, I think there was a real power in putting my naked body into these spaces where others had so often made me feel powerless. I was reclaiming the space for myself.”

“But like most things in life, it’s not that simple,” he continued. “I also think that there was an element of something adjacent to Stockholm syndrome. Of all the places in the world to go and be naked and free — I could go into a forest. I could walk around my apartment naked and feel powerful and beautiful. But I returned to the scene of the crime where the monsters live in the most vulnerable of ways. There was something beautiful and powerful in doing that, and there was something dark and destructive in doing that as well. And it makes so much sense for these images to be connected to this album, because this album is those things. It talks about hope, it talks about being hopeless, it talks about feeling safe and empowered, and then being totally fucked up and putting myself in harm’s way.”

Playful, heartbreaking, raucous, and serene all in turn, Jonny embraces the mess of life in all its facets. This is music that blossoms in contradiction, that offers enough space for its paradoxes to float weightless, catching light. It renders the magic that happens when you fall in love with yourself down to the marrow, when you discover that you’re the font of everything you’ve been seeking. You come home to yourself and the world opens up around you. Jonny offers an invitation to dissolve all the hard lines that separate us from ourselves and, by extension, each other — to soften our shells, to let some tenderness in.

“We are suffering inside,” Pierce says. “I’d love to live in a world where we could all just take off the armor. It’s a little depressing, wearing the armor, not really knowing people, not really being known, not being given the chance to help, or giving yourself the chance to be helped. In making this album, I finally felt strong enough to shed some armor, and in doing that began the process of writing from the deepest parts of my heart.”